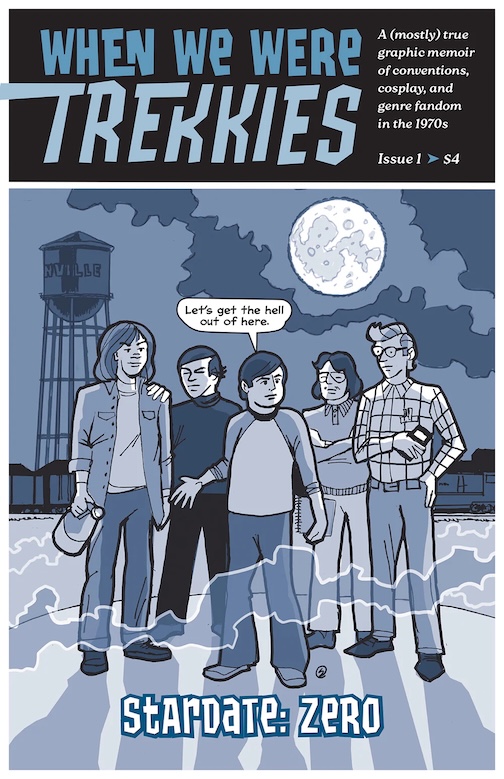

After reading Joe Sikoryak's When We Were Trekkies

you should get his single-issue 1968: A Boy's Odyssey.

It's like a digestive after a meal and provides additional background

for his memoir of science-fiction fandom.

This is about three main events from the same year, 1968: the movies 2001: A Space Odyssey and

Planet of the Apes and the real-life Apollo 8 mission to the moon.

If I had been born 12 or so years earlier, I might have been swept up by

these too. It's a quick read. You should get it!

2025 July 09 • Wednesday

Quimby's in Chicago is still a great place to find new comics. (The Quimby's

in Brooklyn doesn't carry comics because their friend and neighbor

Desert Island Books does that.) I found Joe Sikoryak's "mostly true"

fandom memoir When We Were Trekkies at Quimby's and got hooked

right away.

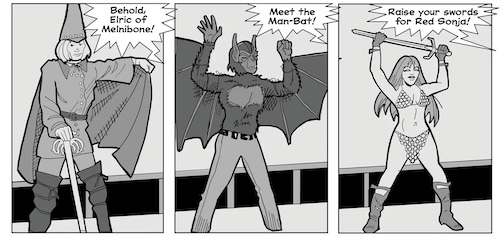

It's about a group of friends in a New Jersey town dominated by an asbestos

factory that's also the engine of the local economy. They're all pretty different

but a love of science fiction in general and Star Trek in particular brings

them together. Of course this enthusiasm also brands them as outsiders. Nobody else

really understands this or even knows about it. After attending their first Star Trek convention and winning prizes

for their home-made costumes—as well as meeting like-minded people and personal

heroes like Nichelle Nichols, William Shatner, Isaac Asimov, Jack Kirby—

fandom becomes a consuming passion. They make different costumes every year, counting on the prize money to

recoup expenses. And of course despite this shared orbit, they still drift off

in different directions as school, work, family, sex pull at them in different

ways.

It's very well written and illustrated. I'd love to know what isn't strictly

"true" in here, how Sikoryak might have smoothed out his story

or added things for structure's sake. You should just buy all ten issues!

2025 July 07 • Monday

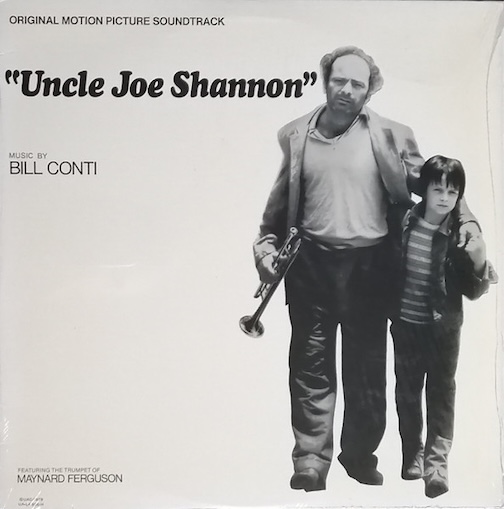

Bill Conti's soundtrack immortality was assured by Rocky. Shortly after that movie,

he also scored Uncle Joe Shannon, written by and starring Rocky's Burt Young.

It's the 864th Soundtrack of the

Week.

The movie is about a trumpet player and Maynard Ferguson was brought on board to supply

the trumpet playing. You hear him almost immediately, after a delicate synth intro

to "Seascape". He sounds great and it's a really nice piece, romantic and sad and ethereal. Violins playing classical music start off "Evening Concert", soon joined by Ferguson

playing an impressive staccato trumpet part. Then Ferguson makes the instrument squeal

and a jazz band come barreling in for an up-tempo swing tune which, of course, features the

trumpet. The classical strings pop back in for a moment but it's really the jazz band's cue. "Fire Tragedy" starts with somber long tones from trumpet and is an elegiac-sounding

piece, atmospheric and quietly assertive. A laidback, bluesy groove appears and Ferguson

plays some beautiful trumpet lines. Flutes start off "Alone Again", which sounds like conventional dramatic underscore but then

the attention shifts to delicate saxophone and piano statements before returning to the flutes. Ferguson then plays trumpet with mute for "Return to the Sea", which has a restrained setting

for his soloing, which builds gradually until the mute comes out and the trumpet gets to soar.

It ends with a dreamy and melancholy piano solo. The main theme, "Uncle Joe", is a change of pace, kind of like big-band disco but of course

with Ferguson taking the lead and playing a ton of great trumpet. It's got that high-energy triumphant

feel that Conti's Rocky music had. There's also some great alto sax playing. The remaining three tracks on the album are source music for "'Goose's Club' Scenes" performed by

an impressive band: Anthony Ortega on tenor sax, Al Aarons on trumpet, Mike Melvoin on piano, Dan

Ferguson on guitar, Chuck Berghoffer on bass and Steve Schaeffer on drums. "Hot Nights" is kind of fusiony disco lounge jazz, "The Goose" is up-tempo bop with great electric

piano playing and "Hard Time" is slightly less up modern jazz with walking bass.

2025 July 04 • Friday

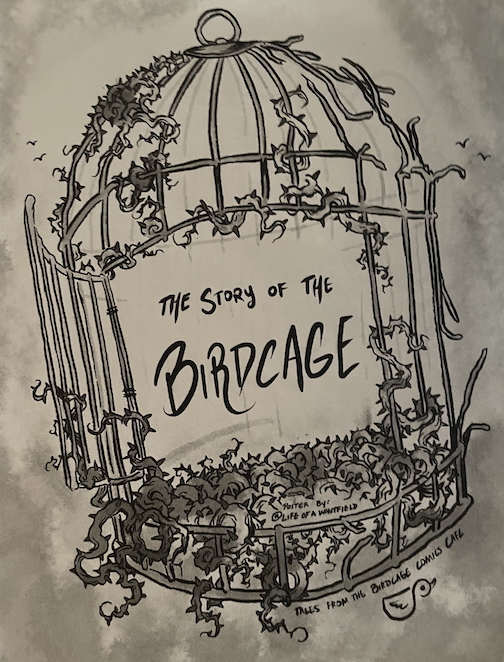

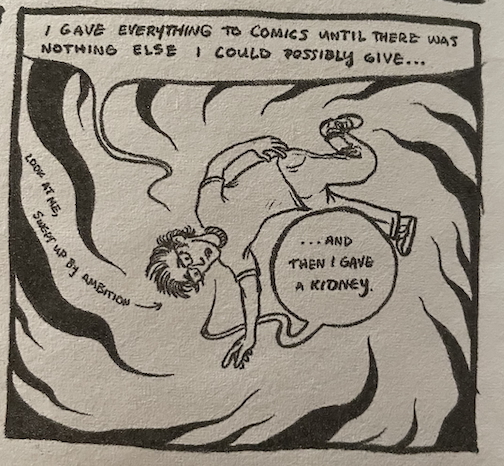

Next time I'm in LA I'm going to drive out to San Bernardino

just to go to Birdcage Comics Cafe. Not only does it

look like a great cafe, it's also a valiant effort to publish

and distribute independent comics. Order something from their website and you might receive

this free mini-comic that tells the story.

It's an inspiring story. Definitely buy some stuff from them! The books are great

and it's a really good cause!

2025 July 02 • Wednesday

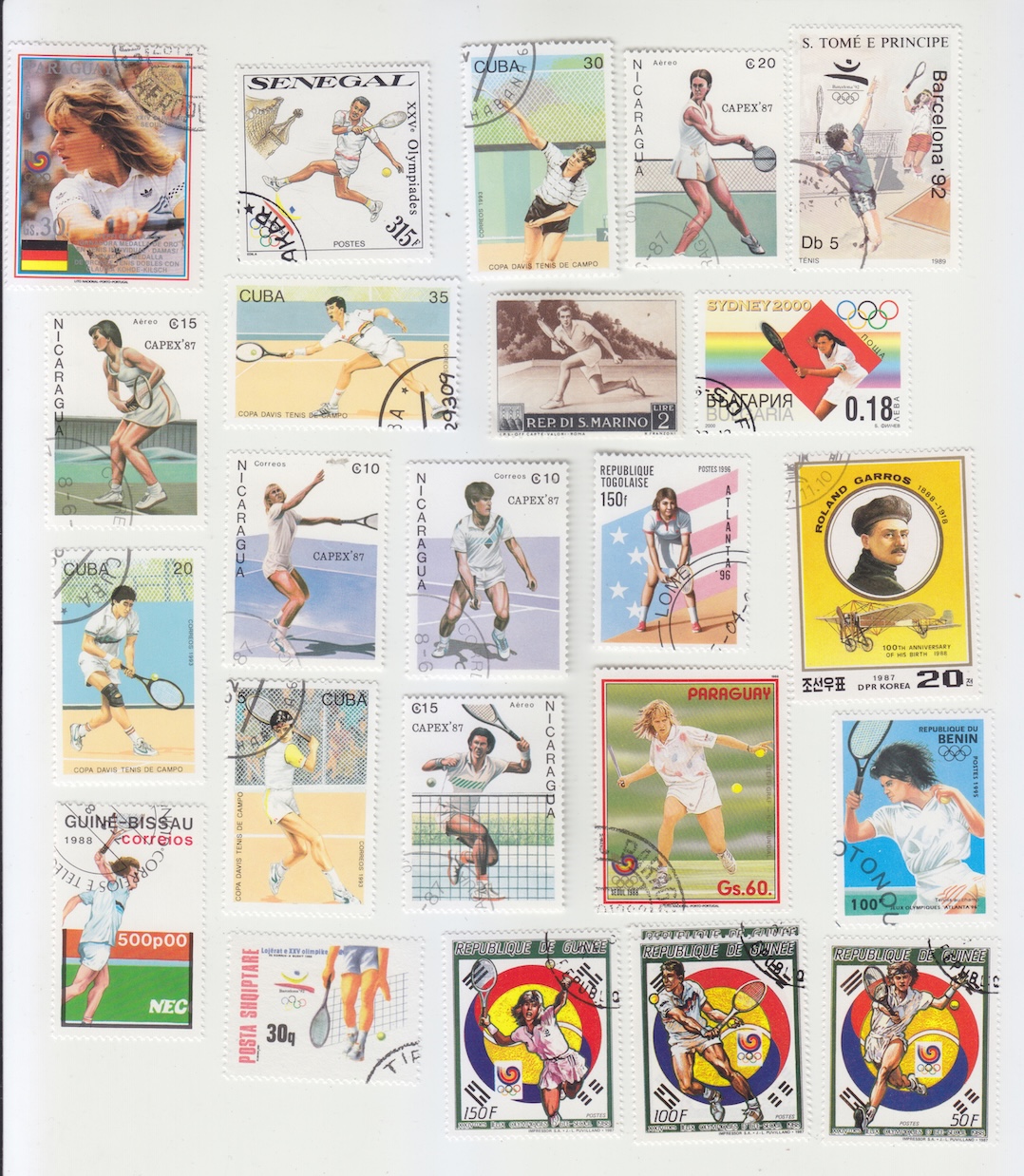

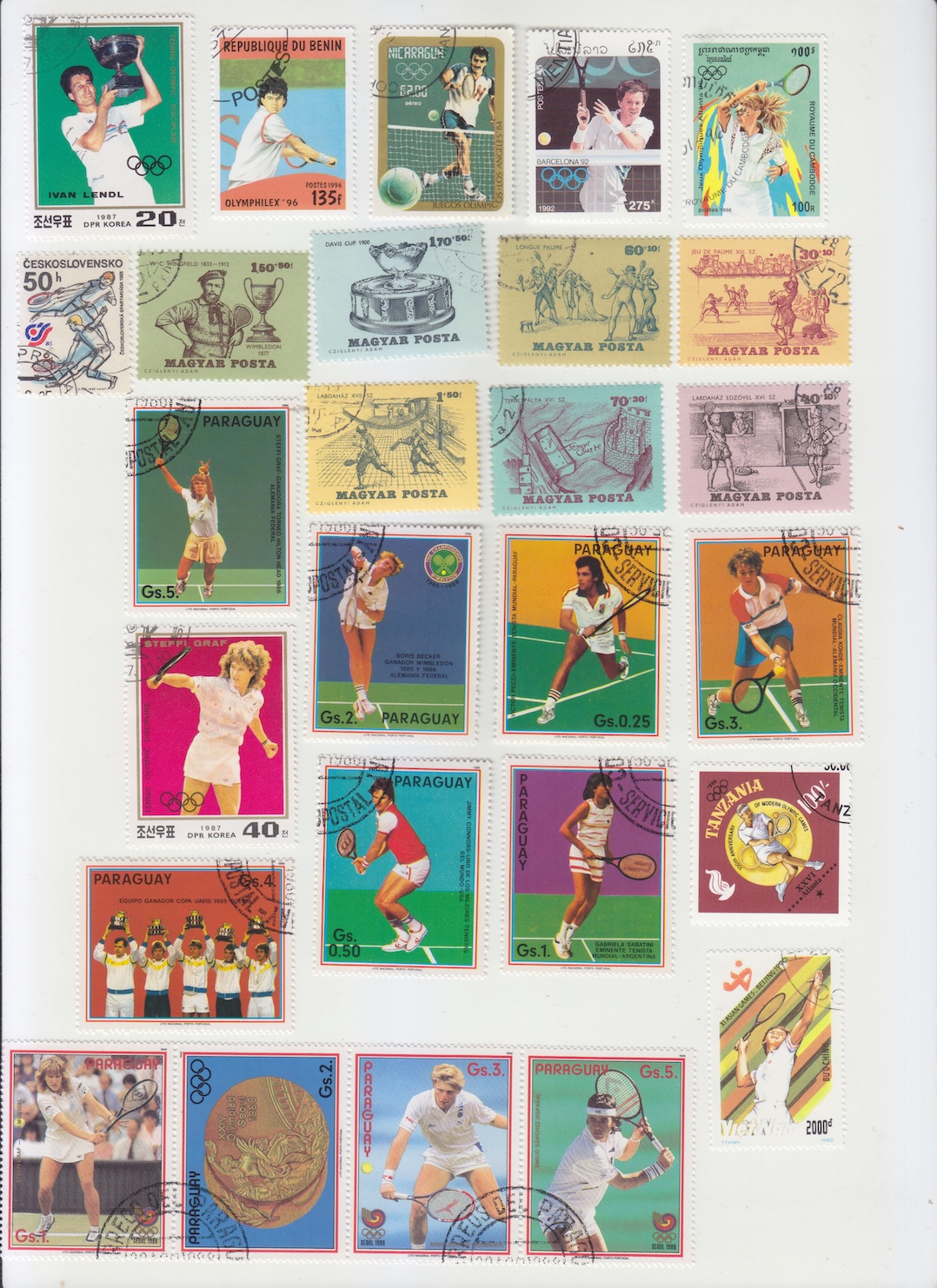

Wimbledon just started so here's a bunch of tennis stamps.

APPEARANCES

APPEARANCES